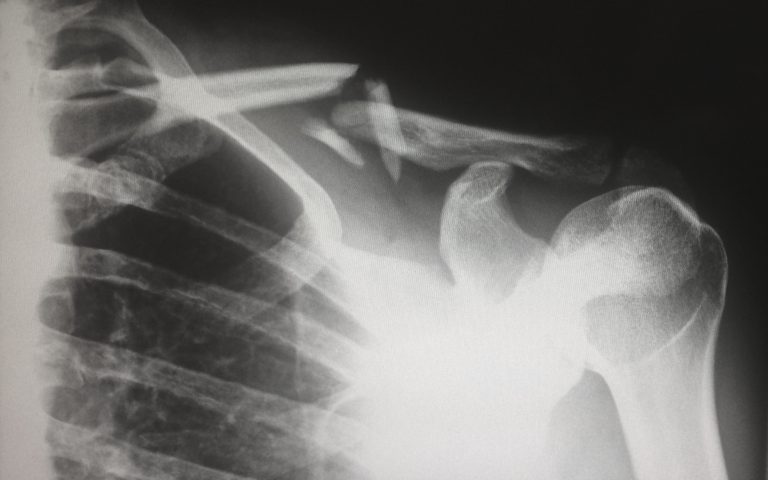

The coronavirus epidemic is exposing the pain points of the American health care system. There is now a huge demand for health care’s frontline—the primary care physicians. Then again, even before the outbreak reached a fever pitch, the country was already experiencing a shortage in health care personnel, primarily with doctors. Back in July, there were already reports circulating that America will incur a devastating doctor shortage. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) confirmed it by stating that the U.S. could face a shortfall of between 21,000 and 55,000 primary care physicians by 2023. Couple that statistic with the sudden spike in demand due to the COVID-19 outbreak, making this challenge seem insurmountable.

However, there might be a way to deliver enough primary care to the U.S. population in the next decade, even with changes in demand, without adding thousands of physicians to the current expected supply. The Department of Health and Human Services estimates than by 2025, the U.S. will have around 190,000 non-pediatric primary care doctors. Assuming normal patient panels (around, 2000), then there’s reason to believe that they can accommodate 380 million people vs. the U.S. population estimate of 272 million people. Estimates from other institutions like JAMA even put the figures higher—600 million people, which is almost twice today’s population.

The disconnect between the expected capacity vs the actual numbers may be because of uneven distribution, incomplete coverage, inconvenient hours, inflexible care models, and payer aversion. For starters, some regions in the country experience a mismatch of supply and demand. For example, there are not enough doctors practicing in rural or impoverished areas.

The uninsured rate is also rising; the previous 13% has recently jumped to 14% of the population, meaning there are more and more people who can’t afford access to primary care. Plus, in many markets, primary care still isn’t available around the clock. People living in these areas don’t have access to doctors during evenings, nights, and weekends.

What’s more, there are many markets that still rely on primary care physicians to deliver primary care in a physician’s office, even though physician assistants and nurse practitioners are very much capable of delivering primary care of equally high quality, sometimes even at a lower cost. Another contributing factor is payer aversion, with some practices limiting the number of new patients they take on from Medicare, Medicaid, and other public programs, because such patients are deemed unprofitable.

When considering these factors, none of them point to the shortage of doctors. In fact, what they suggest is the health care system is mismanaging the current physician population. There’s a perceived shortage because the system is inefficient in many aspects: care models, labor practices, sites of care, and process.

To mitigate this problem, the health care system should abandon a one-size-fits-all approach to primary care and embrace different care models to accommodate different types of patients. Recent Advisory Board research and analysis suggest that there should be a better use of PCPs targeted at specific populations, greater use of non-physician labor where appropriate, and a broader deployment of technology to increase access to primary care.

To stay updated with the latest news in the medical industry, browse our website.