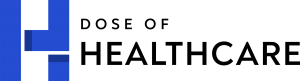

Artificial, fully-functioning organs that can be implanted in human bodies may be a reality sooner than you think. In the past couple of years, there have been significant advancements in 3D printing that can be a game-changer to the entire healthcare industry.

Back then, scientists and researchers have only been utilizing 3D printers to create dental implants, prosthetics, and models for surgeons to practice with prior to going on actual surgery with patients. But now, there has been much headway, allowing them to move beyond printing plastics and metals and start printing cells that can form living human tissues.

While the current technology is not capable of printing fully functional organs just yet, recent developments show great promise that could lead towards that eventuality. It is now possible to craft pieces of tissue that can be useful in testing drugs and understanding the body’s extremely complex biology.

And soon enough, there may come a time that 3D printed organs can be implanted to patients who are in dire need of transplants. Instead of waiting days, months, or even years for a suitable donor, or risk their body rejecting a transplanted organ, patients in critical condition can have customized printed organs that match their body chemistry.

When it comes to attempting to 3D print organs, scientists have only so far tried printing mini organoids and microfluidics models of tissues called organs of chips. Both have contributed to navigating the function of the human body. There are also some models that are used by pharmaceutical companies to test drugs before proceeding with animal studies and clinical trials.

The tricky part is constructing organs that mimic the complex structural characteristics and functions of human tissues. However, according to Robby Bowles, a bioengineer at the University of Utah, there are already institutions trying to 3D print organs like ears to help children who had congenital disabilities that rendered their ears underdeveloped. “There are a number of companies who are attempting to do things like 3-D print ears,” he said. The transplants are “kind of the first proof of concept of 3-D printing for medicine.”

Another massive hurdle is figuring out how the printed organ can avoid immune rejection and eliminate the need for patients to take immunosuppressive drugs. The ultimate goal is to 3D print organs composed of cells that a patient’s immune system could recognize as its own.

Such organs can be built from patient-specific stem cells, but there’s another catch: getting the cells to automatically differentiate into the subtype of a mature cell that is needed to create a particular organ. “The difficulty is kind of coming together and producing complex patternings of cells and biomaterials together to produce different functions of the different tissues and organs,” Bowles explained.

Scientists are trying to imitate the patterns by printing cells into hydrogels or other environments with molecular signals and gradients. Hopefully, this technique could urge the cells to organize themselves into lifelike organs.

They have not been successful yet, but researchers are able to create patches of tissue that replicate portions of certain organs. The only thing missing is the complexity or cell density of the full organ. It’s a good thing that in some cases, patches could be an effective treatment.

There’s still a ways away to printing fully functional and implantable organs, but the recent breakthroughs prove that it’s not an impossibility.

Browse our website today for more news in the medical industry.